Q. Comment on the nature of rural society in the peninsular India?

Rural society in

peninsular India, like other parts of the Indian subcontinent, has historically

been structured around complex systems of social, economic, and cultural

organization. This rural landscape has been shaped by a variety of factors,

including geographical diversity, agricultural practices, feudal and

caste-based hierarchies, and the influence of successive empires and colonial

rule. Over the centuries, the rural communities in peninsular India have

undergone transformations, influenced by the shifting dynamics of land

ownership, social relations, religious beliefs, and external economic forces.

While there are distinct regional differences across peninsular India, there

are also common threads that tie rural societies together in the broader historical

context. In this exploration, the nature of rural society in peninsular India

is analyzed from the perspectives of its economic structure, social

organization, political institutions, and the evolving interactions between

local communities and external forces such as state control, colonialism, and

globalization.

Peninsular India, a

region defined by the Southern portion of the Indian subcontinent, is

characterized by its diverse geographical landscape that includes the Western

Ghats, Deccan Plateau, and coastal plains. This geographical diversity

significantly influenced the agricultural practices, economic activities, and

settlement patterns that formed the backbone of rural society in the region.

The agrarian economy, based primarily on subsistence farming, was the mainstay

of rural life across peninsular India.

In the early period, the

agricultural practices in the region were influenced by local ecosystems. The

relatively fertile Deccan Plateau, especially in regions like Karnataka, Andhra

Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, was conducive to the cultivation of crops such as

rice, pulses, and cotton, while the coastal regions of Kerala and the Konkan

coast developed a thriving economy based on the cultivation of rice, coconut,

and spices. The introduction of irrigation, particularly through tanks, wells,

and canals, became an integral part of rural society in the peninsular region.

These systems were developed both under indigenous kingdoms and during the

period of Islamic rule, especially during the rule of the Vijayanagara Empire

(14th-17th centuries), which constructed an extensive network of irrigation

systems.

The economy of rural

society was primarily agrarian, but it also included a variety of other

economic activities, such as animal husbandry, fishing, weaving, pottery, and

local crafts. Rural artisans and laborers often operated in close-knit

communities, producing goods for local consumption or trade. In addition to

agriculture, the rural economy was supported by village industries such as

textile weaving (especially in Tamil Nadu), metallurgy, and pottery, which were

essential components of local economies.

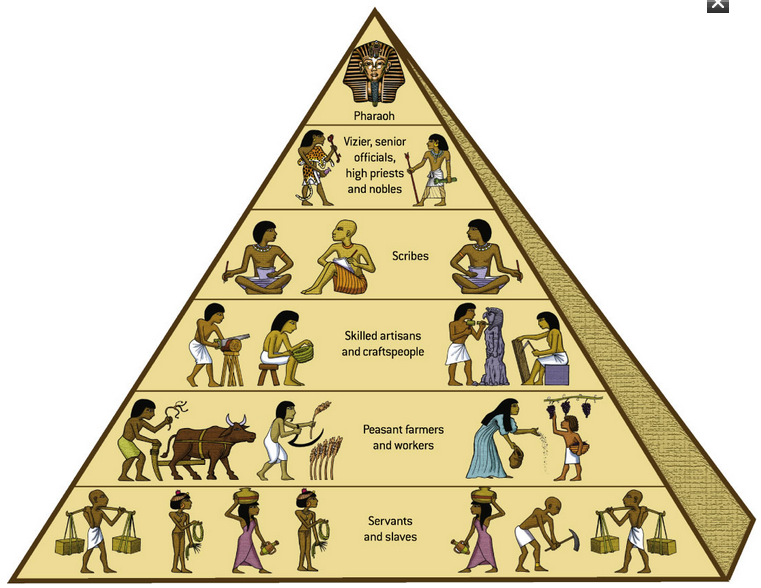

Social

Organization and Caste System

The social structure of

rural peninsular India was deeply influenced by the caste system, a

hierarchical social order that structured virtually all aspects of life. The

caste system in peninsular India was more rigid in some areas and less so in

others, but it provided the foundation for social organization, determining who

could work in which occupations, whom one could marry, and even the degree of

social mobility an individual could hope to achieve. Within this system,

Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras formed the four broad varnas, with

the Dalits (historically known as untouchables) existing outside of the varna

hierarchy.

The caste system, in its

various forms, played a significant role in organizing the rural economy. In

many rural areas, caste occupations were inherited, and each caste had its

specific role within the local economy. For example, Brahmins were associated

with religious and educational roles, while Sudras typically worked in

agricultural labor or as artisans. The Dalits, occupying the lowest position in

the social hierarchy, were often relegated to menial labor, such as cleaning,

handling animal carcasses, and working with leather. In some regions of

peninsular India, the caste system was more flexible, with people from lower

castes being able to gain some degree of upward mobility, particularly through

acquiring wealth or through marriage alliances.

Apart from the caste

system, the role of family, kinship, and village panchayats also played a key

role in the social organization of rural India. The family unit was the basic

social and economic unit, and in many cases, joint family structures were prevalent,

particularly in the southern parts of the country. These families were often

extended and organized around a common economic activity, such as farming, and

were typically patriarchal, with the eldest male member of the family having

the authority to make decisions regarding property, marriage, and economic

affairs.

The village panchayat,

which acted as the local governing body, played an essential role in managing

social relations and resolving conflicts. The panchayat was typically composed

of respected elders who made decisions on issues ranging from land disputes to

social conduct. This institution of village self-governance, however, was often

influenced by external powers, especially during the colonial period when the

British attempted to centralize control over rural society and weaken

traditional village governance structures.

Feudalism and Land

Ownership

A defining feature of

rural society in peninsular India during the medieval period was the dominance

of feudal relationships. Under the influence of both Hindu and Islamic rulers,

peninsular India saw the development of a feudal system that was built around

landownership and tribute. Feudal lords, often local aristocrats or landowners,

were responsible for overseeing the agricultural production of their estates,

and peasants, or "rayats," worked on these lands under various forms

of tenancy, including sharecropping, fixed rents, and labor services.

The state or the ruling

elite controlled the land and its revenue, and this concentration of

landownership in the hands of a few elite groups was central to the feudal

system. The rural peasantry, most of whom were cultivators, were tied to the

land, and their lives were shaped by the economic demands of the feudal lords.

In exchange for their labor or a portion of their agricultural produce,

peasants were often granted limited security of tenure. However, this system

was fraught with exploitation, and rural society was structured in a way that

kept the peasantry in a state of subordination to the feudal lords.

Feudalism also had an

important impact on the social fabric of rural peninsular India. Landlords and

regional rulers often had considerable social influence in their local areas,

and this influence extended to shaping religious and cultural practices. Many

regional rulers, especially in southern India, built temples and supported

religious institutions, which acted as centers of social and economic life. For

example, in the Vijayanagara Empire, the rulers built massive temples that

became centers of economic activity, employing thousands of workers and

supporting artisans, priests, and scholars. These temples also served as social

spaces where the community could gather for religious and social events.

The British colonial

rule, which formally began in the 18th century, altered the feudal structure of

rural society in peninsular India. The colonial administration's land revenue

policies, such as the Permanent Settlement of 1793, which was implemented in

Bengal and spread across much of India, disrupted traditional landholding

patterns and led to the consolidation of landownership in the hands of a few

landlords or zamindars. This shift contributed to the impoverishment of the

rural peasantry, as landlords were primarily focused on extracting the maximum

possible revenue from the land, often at the expense of the peasantry’s

well-being. The colonial state also created new forms of landownership and

legal systems, which marginalized traditional forms of rural governance and

weakened the power of local institutions such as the panchayats.

Colonial Impact

and Changes in Rural Society

The colonial period had a

profound impact on rural society in peninsular India. British colonial policies

were largely focused on extracting resources from rural areas, and this

exploitation was deeply intertwined with changes in land tenure systems, agriculture,

and rural industries. The colonial administration’s focus on cash crop

production led to the expansion of crops like indigo, cotton, and opium, which

were grown at the expense of food crops. The introduction of new technologies

such as railways and irrigation systems, while facilitating trade and economic

growth in certain sectors, also deepened the rural dependency on the colonial

economy.

The disruption of

traditional rural economies during the colonial period had significant social

consequences. While the British sought to modernize India’s infrastructure,

their policies often led to the decline of local industries and the

impoverishment of rural communities. Traditional crafts, such as handloom

weaving and pottery, were particularly affected by the influx of cheap

British-manufactured goods, which flooded the Indian market. Many artisans and

rural workers were forced into poverty as their traditional livelihoods were

undermined by foreign competition.

The monetary economy

introduced by the British also had a long-lasting effect on rural society.

Before colonial rule, many rural communities operated in a barter economy, with

goods exchanged directly for other goods. However, the colonial introduction of

money as a medium of exchange and the monetization of land revenue systems led

to the deepening of class divisions. Wealthy landlords, moneylenders, and

traders who dealt in cash often exploited peasants, who were forced to take

loans and pay exorbitant interest rates. The increased reliance on money in the

rural economy created new forms of economic inequality and social exploitation.

The rural economy in

peninsular India was further destabilized by periodic famines, some of which

were exacerbated by British policies. The Great Famine of 1876–78, for example,

devastated large parts of southern India, leading to millions of deaths. British

administrators often ignored or mismanaged relief efforts, with devastating

consequences for rural communities. These famines, combined with the broader

colonial economic policies, left many rural areas impoverished and vulnerable

to external economic pressures.

The Nationalist

Movement and Rural Society

The rise of the

nationalist movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had important

implications for rural society in peninsular India. The Indian National

Congress, which became the central political force in the struggle for

independence, sought to mobilize rural populations against colonial rule. While

rural India was not the primary base of the nationalist movement, its support

was crucial for the success of the independence struggle. Mahatma Gandhi’s

focus on rural India and his campaigns, such as the Champaran Satyagraha (1917)

and the Salt March (1930), were key moments in the nationalist movement’s

engagement with rural society. Gandhi’s emphasis on self-reliance, rural

development, and the abolition of untouchability resonated with many rural

communities, who were suffering from the exploitation of both the colonial

state and the upper castes.

At the same time, the

rise of rural activism and peasant movements, such as the Telangana

Rebellion (1946–51) and the Peasant Movements in Tamil Nadu, were

expressions of discontent with the feudal and colonial exploitation of rural

labor. These movements sought to challenge the entrenched systems of

landownership, caste-based discrimination, and economic inequality that had

defined rural society for centuries. However, the real transformation of rural

society in post-independence India would come later, with land reforms and the

Green Revolution of the 1960s, which sought to modernize Indian agriculture and

improve the condition of rural communities.

Conclusion

The nature of rural

society in peninsular India was historically shaped by a complex interplay of

geography, economy, caste, landownership, and political authority. It was an

agrarian society, deeply rooted in agricultural practices and organized around caste-based

hierarchies. The feudal land tenure systems that prevailed for much of the

medieval and early modern periods entrenched inequalities and created a rigid

social structure. The colonial period exacerbated these social and economic

disparities, with policies that focused on resource extraction, economic

dependency, and the disruption of traditional industries.

However, rural society in

peninsular India also displayed resilience and adaptability, with local

communities continuing to practice indigenous forms of agriculture, governance,

and cultural traditions. The rise of nationalist movements in the 19th and 20th

centuries also brought attention to the struggles of rural populations, with

leaders like Gandhi advocating for rural development and the empowerment of the

peasantry. The post-independence period has seen efforts to address the

inequities in rural society, although challenges persist in the form of land

inequality, poverty, and regional disparities. The history of rural society in

peninsular India is thus a story of both exploitation and resistance,

continuity and change, and a testament to the enduring importance of rural

India in shaping the country’s broader historical narrative.

0 comments:

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.