Q. Examine totemism as an elementary form of religion.

Totemism, as an

elementary form of religion, has been a subject of significant anthropological

and religious scholarship, offering profound

insights into the early stages of human religious development. The concept of

totemism refers to a system of beliefs that connects individuals or groups with

specific natural objects, animals, plants, or celestial bodies, referred to as

totems, which are seen as emblematic or sacred. These totems serve as symbols

of kinship, spiritual power, and ancestral identity within a group, and often

play a central role in the group’s social and religious organization. The study

of totemism has been particularly influential in understanding the relationship

between religion, culture, and society in early human history.

Totemism can be

broadly understood as a belief system where certain groups of people associate

with particular animals, plants, or natural phenomena, considering these

entities as their ancestors, protectors, or representatives. The term

"totem" itself comes from the Ojibwe language of Native Americans,

where it means "a family, clan, or tribe's symbol or emblem,"

although the concept is found across various cultures globally.

Totemism is not

simply a form of animism, where objects in nature are imbued with spirits, but

rather it involves a deeper symbolic and spiritual connection between humans

and the natural world. A totemic entity may serve as a protector, guide, or

ancestor for the group, often influencing social structures, rituals, and even

moral codes. In some cases, individuals are born into specific totemic groups,

and this determines their social roles and their relationships with other

groups within the broader community.

Historical Development and Scholarly Perspectives

The study of

totemism as an elementary form of religion has been particularly associated

with the work of early anthropologists such as Émile Durkheim, James Frazer,

and Sigmund Freud, who each attempted to understand the role of totemism in the

development of religious thought and social cohesion. Their works helped shape

the modern understanding of totemism as a foundational element of religious

life in early human societies.

Durkheim’s

Contribution to Totemism

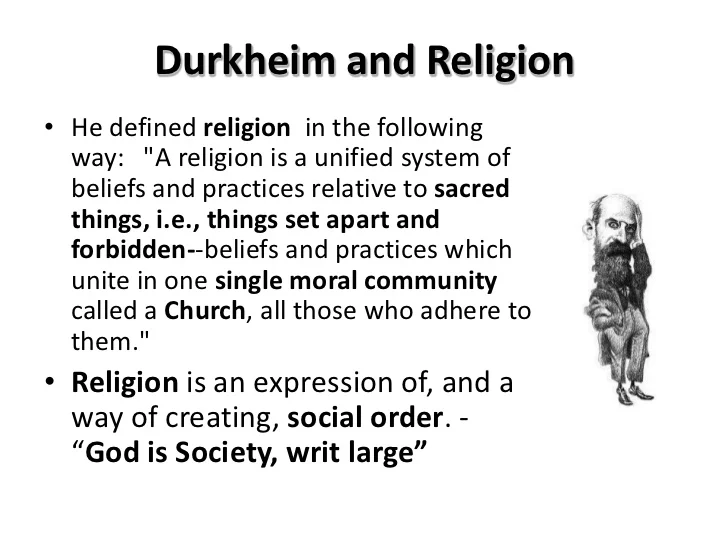

Émile Durkheim, in

his seminal work The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912),

proposed that totemism was one of the most fundamental and earliest forms of

religion. Durkheim argued that totemism provided a model for understanding the

origins of religious thought and practice in human societies. For Durkheim, the

totem was not just an animal or plant, but a symbolic representation of the

social group itself. The totem symbolized the unity and solidarity of the

group, and the rituals associated with totemism reinforced this collective

identity. According to Durkheim, religious beliefs and practices in totemism

were not focused on individual deities, but rather on the collective

consciousness of the group.

Durkheim's

analysis emphasized the social function of religion, suggesting that the belief

in a totem was closely linked to the maintenance of social cohesion. Totemic

rituals, which often included feasts, dances, and sacrifices, were ways for

individuals to reaffirm their belonging to the group and to demonstrate their

collective power. In this context, Durkheim argued that totemism was less about

the worship of specific animals or plants, and more about the worship of

society itself.

Frazer and the

Evolutionary Approach

James Frazer, a

contemporary of Durkheim, took a more evolutionary approach to the study of

religion, including totemism. In his famous work The Golden Bough

(1890), Frazer suggested that totemism was an early stage in the evolution of

religious thought, which eventually gave way to more complex forms of religion,

such as polytheism and monotheism. According to Frazer, early humans initially

regarded certain animals or plants as sacred or powerful, and these totems

played a central role in the early stages of religious development.

Frazer’s theory

emphasized the role of magic in early religious practices, suggesting that

totemic beliefs were tied to the desire to control or influence nature. For

example, in some totemic societies, individuals believed that by imitating the

totemic animal’s behaviors or traits, they could gain its strength or power.

Over time, Frazer argued, religious thought evolved, and the practice of

totemism became increasingly formalized and integrated into the social

structure of communities.

Freud’s

Psychoanalytic Interpretation

Sigmund Freud, in

his psychoanalytic theory of religion, also touched upon the concept of

totemism, albeit in a different context. In Totem and Taboo (1913),

Freud proposed that totemism was connected to the unconscious desires and fears

of early human societies. Freud’s theory centered on the idea that totemism was

a symbolic expression of the Oedipus complex, in which early humans,

particularly men, harbored unconscious desires for their mothers and hostility

toward their fathers. The totem, according to Freud, represented a kind of

substitute for the father figure, and the totemic animal or plant was seen as a

protective symbol that helped to alleviate these unconscious conflicts.

Freud’s analysis

of totemism was controversial and has been widely criticized for its

reductionist and psychoanalytic approach. Nevertheless, his work contributed to

the broader discourse on totemism by highlighting the psychological dimensions

of early religious practices.

Totemism and Social

Organization

One of the most

important aspects of totemism is its relationship to social organization. In

many totemic societies, individuals are born into specific clans or groups,

each associated with a particular totem. These totemic groups often form the

basic units of social organization, and membership in a clan or group is

determined by the ancestral connection to the totem. This social structure

serves as a framework for social interaction, as individuals are often

prohibited from marrying within their totemic group, which helps to ensure

social cohesion and prevent incest.

Totemism also

plays a role in defining social roles and responsibilities within a group. In

some societies, individuals with certain totems may be assigned specific duties

or tasks, based on their association with the totemic animal or plant. For

example, those with a wolf totem may be seen as warriors or hunters, while

those with a bear totem might be regarded as healers or spiritual leaders. The

totemic system thus serves to create a structured and hierarchical society,

with different groups having distinct roles and responsibilities.

In addition to its

social functions, totemism often intersects with ideas about ancestry and

kinship. The totem serves as a symbol of ancestral identity, and the group’s

history and traditions are often linked to the totemic entity. Rituals,

ceremonies, and myths associated with the totem are central to the group’s

collective memory, helping to preserve cultural practices and reinforce the

importance of shared ancestry.

Totemic Rituals and

Beliefs

Totemism is deeply

intertwined with religious rituals and beliefs, which are often centered around

the veneration of the totemic entity. Rituals may involve offerings,

sacrifices, dances, and feasts, all of which serve to honor the totem and

strengthen the connection between the group and its totemic protector. These

rituals are often performed during significant events, such as seasonal

transitions, rites of passage, or during moments of crisis, when the group

seeks divine favor or protection.

One of the most

well-known aspects of totemism is the prohibition on killing or eating one’s

totem animal, which is often seen as sacred. This taboo reinforces the belief

in the totem’s spiritual power and serves to maintain the reverence and respect

for the totemic entity. Violating this taboo is believed to bring misfortune or

punishment upon the individual or group, further solidifying the authority of

the totem.

In addition to

ritual practices, totemism is often accompanied by elaborate myths and legends

that explain the origins and significance of the totemic entity. These myths

often describe the creation of the world, the relationship between humans and

the natural world, and the role of the totem in shaping the group’s identity.

Totemic myths can serve as a moral framework for the community, providing guidance

on how individuals should live and interact with one another and the world

around them.

Totemism in

Different Cultures

While totemism is

found in many different cultures across the world, it takes on unique forms

depending on the specific historical, cultural, and geographical context. For

example, in Indigenous Australian societies, totemism is central to the concept

of Dreamtime, the mythical period of creation. Australian Aboriginal groups

believe that their ancestors emerged from the natural world and took on the

forms of animals, plants, or natural phenomena. These totemic beings are

revered and celebrated through rituals and ceremonies, which serve to maintain

the spiritual connection between the people and the land.

Similarly, among

Native American cultures, totemism plays a central role in the organization of

clans and the establishment of social order. The totemic animals are often

regarded as ancestors or spiritual guides, and they are incorporated into the

myths, rituals, and art of these societies. In some Native American groups,

totem poles are carved to represent the clan’s totemic ancestors, serving as

both symbolic and physical markers of the group’s identity.

In African

societies, totemism is often linked to ancestral worship and the belief in the

spiritual power of nature. In many African cultures, individuals are born into

specific totemic groups and inherit the characteristics or qualities associated

with their totem. Totemism is also closely tied to agricultural practices, with

certain plants or animals believed to possess special powers that influence the

fertility of the land.

Criticisms and

Contemporary Perspectives

The study of

totemism has not been without its critics. Some anthropologists argue that the

concept of totemism is overly simplistic and fails to account for the

complexity and diversity of religious beliefs in different cultures. Critics

also point out that totemism as a formal category may not be applicable to all

societies, and the term "totemism" itself can be problematic due to

its Western origins and the colonial contexts in which it was applied.

Moreover,

contemporary anthropologists and religious scholars have moved away from the

idea that totemism represents a static or primitive stage in the evolution of

religion. Instead, totemic beliefs and practices are now seen as part of a

dynamic and evolving religious landscape that cannot be reduced to a singular,

linear progression. The study of totemism, therefore, must take into account

the historical, cultural, and social factors that shape religious beliefs and

practices.

Conclusion

Totemism, as an

elementary form of religion, offers valuable insights into the ways in which

early human societies understood the world, organized themselves socially, and

developed spiritual beliefs. Through its connection to nature, ancestry, and

social cohesion, totemism represents a profound form of religious expression that

predates many of the more complex and institutionalized religions that

followed. While the study of totemism has evolved over time, with scholars

offering different interpretations and critiques, it remains a critical area of

research for understanding the development of religious thought and the role of

religion in human society.

0 comments:

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.