Q. Critically analyse the major concerns of Hemingway in his short stories.

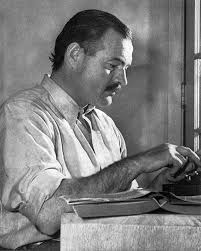

Ernest Hemingway, one of the most significant American writers of the

20th century, is renowned for his minimalist style and the profound themes

explored in his works. His short stories, while diverse in subject matter,

collectively explore a variety of major concerns such as the complexities of

human existence, the nature of masculinity, the impact of war, the tension

between life and death, and the search for meaning in a seemingly indifferent

universe. These themes are underscored by his distinctive writing style, which

is characterized by economy of language, an emphasis on subtext, and the use of

what has been called the "Iceberg Theory," wherein much of the

emotional weight of a story is implied rather than explicitly stated. In this

analysis, we will explore how these concerns are reflected in Hemingway's short

stories, examining key examples and drawing connections between his life

experiences and literary output.

In “A Way You’ll Never Be,” the protagonist, Nick Adams, is similarly

haunted by his experiences during the war, yet the story also explores the

broader psychological effects of trauma. Hemingway’s portrayal of soldiers as

victims of war suggests that the physical and emotional wounds of combat are

inescapable. In both stories, the authors seem to imply that the psychological

damage caused by war is not only personal but societal, affecting the

relationships and communities that soldiers return to.

In addition to war, Hemingway’s stories also grapple with the theme of masculinity and its complexities. The traditional notion of masculinity, often characterized by physical strength, stoicism, and dominance, is examined critically in many of his works. For example, in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” the protagonist struggles with his sense of inadequacy and fear, particularly in relation to his wife, who seems to see him as weak and ineffectual. Macomber’s journey throughout the story can be interpreted as an exploration of the pressures of conventional masculinity, with his ultimate act of courage (which leads to his death) marking a tragic attempt to reconcile his internal conflicts with societal expectations of manhood. Hemingway frequently explores the tension between emotional vulnerability and the societal pressure for men to display toughness and emotional restraint. The complicated relationships between men and women also come into play in this context, as Hemingway often depicts female characters who challenge or question the traditional masculine ideals of strength and bravery.

Hemingway’s interest in masculinity is not limited to the interaction

between men and women, however. In stories like “Big Two-Hearted River,”

Hemingway examines a more intimate, personal kind of masculinity, one that is

tied to solitude, introspection, and the relationship between a man and nature.

In this story, Nick Adams, a recurring Hemingway protagonist, goes fishing in

the woods to recover from the emotional and physical scars of war. The

narrative, largely devoid of dialogue, focuses on Nick’s solitude and his quiet

determination as he engages in a meditative, almost ritualistic act of fishing.

Here, Hemingway portrays masculinity as something private and self-contained, a

means of finding solace and meaning in the midst of suffering. This theme is

further reflected in “The Killers,” where the characters, particularly the

professional killers, embody a detached and cold masculinity. Their

relationship to violence and death is portrayed as clinical and emotionless,

reflecting Hemingway's exploration of the ways in which men respond to danger

and death with stoicism, often masking fear or vulnerability.

Alongside masculinity, Hemingway frequently deals with the tension

between life and death, exploring the fragility of human existence and the

inevitability of mortality. In stories like “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” the

inevitability of death is a central theme. The protagonist, Harry, reflects on

his life and his past decisions as he faces the end of his life from a

gangrenous infection. His thoughts, regrets, and longing for a more meaningful

existence are juxtaposed with the beauty and indifference of nature,

represented by the snow-covered peak of Mount Kilimanjaro. Hemingway’s

exploration of death in this story highlights the harsh realities of life and

the human desire for transcendence. However, the cold indifference of nature,

which looms large throughout the story, suggests that death is an inevitable

part of the natural order—one that cannot be escaped through regret or

self-reflection.

In “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” the theme of existential despair and

the search for meaning in a world that seems indifferent to human suffering is

explored through the experiences of two waiters in a café. The older waiter,

who is more sympathetic to the old man’s suffering, expresses a deep

understanding of the isolation and loneliness that pervade human existence. The

story is deeply existential in nature, presenting a worldview in which life’s

meaning is elusive and often fleeting, but the need for comfort and

understanding remains a powerful force. Hemingway’s portrayal of the older

waiter’s reflection on the importance of a “clean, well-lighted place”

emphasizes the human need for solace in the face of life’s darkness and

uncertainty.

The theme of the search for meaning is also central to Hemingway’s

treatment of relationships and love. In stories like “Hills Like White

Elephants,” Hemingway explores the complexities of communication and

misunderstanding between men and women. The story’s central couple, who are

debating whether to have an abortion, engage in a tense and elliptical

conversation that reveals more about their emotional distance than their actual

topic of discussion. Hemingway’s ability to suggest the internal emotional

lives of his characters through dialogue, or the lack thereof, is one of the

hallmarks of his writing. In this story, the tension between the man and the

woman reflects the broader existential dilemma of human relationships: the

difficulty of truly understanding one another and the profound disconnect that

often exists between individuals.

While Hemingway’s writing is often seen as stoic and sparse, it is also

filled with subtle emotional depth, particularly in his portrayal of human

relationships. The struggles between individuals—whether it’s the tension

between a man and a woman, the alienation of a soldier returning from war, or

the solitary man’s confrontation with his own mortality—are all central

concerns in Hemingway’s short stories. Hemingway’s characters, regardless of

their specific circumstances, often grapple with the desire for connection, the

search for meaning, and the need to confront the realities of suffering and

loss. These themes transcend the specific contexts of his stories, offering a

universal commentary on the human condition.

Furthermore, Hemingway’s writing often emphasizes the idea of grace

under pressure, a concept closely tied to the notion of heroism. In many of his

stories, the protagonists demonstrate remarkable endurance and stoicism in the

face of adversity. For example, in “The Old Man and the Sea,” the aging

fisherman Santiago engages in a solitary battle with a giant marlin,

demonstrating perseverance, strength, and resilience despite his physical

limitations. Similarly, in “The Killers,” the character of Ole Andreson

embodies a quiet, resigned bravery as he faces death at the hands of hitmen.

Hemingway’s focus on the ability to endure hardship with dignity reflects his

belief in the importance of personal integrity and the capacity for individuals

to confront their fate with courage and honor, even when the outcome is

inevitable.

Finally, Hemingway’s themes are also influenced by his writing style,

which has been described as sparse, direct, and economical. His characteristic

use of short, simple sentences and understated prose mirrors the emotional

restraint and control exhibited by his characters. Hemingway’s style reflects

his belief in the importance of what is not said—his “Iceberg Theory”—where the

bulk of a character’s emotions and motivations are submerged beneath the

surface of the narrative. This minimalist approach forces readers to engage

actively with the text, interpreting the subtext and filling in the gaps

between the lines. The result is a writing style that is both subtle and

powerful, allowing for a deep exploration of complex emotional and

philosophical themes.

In conclusion, Hemingway’s short stories address a range of profound

concerns, including the impact of war, the complexities of masculinity, the

fragility of life, the inevitability of death, and the search for meaning in an

indifferent world. These themes are reflected not only in the content of his

stories but also in his distinctive writing style, which emphasizes restraint,

subtext, and emotional depth. Through his portrayal of characters who confront

suffering, isolation, and existential dilemmas, Hemingway offers a poignant

meditation on the human condition. His works continue to resonate with readers

today, serving as a testament to the power of storytelling to explore the

complexities of life and death, meaning and existence.

0 comments:

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.